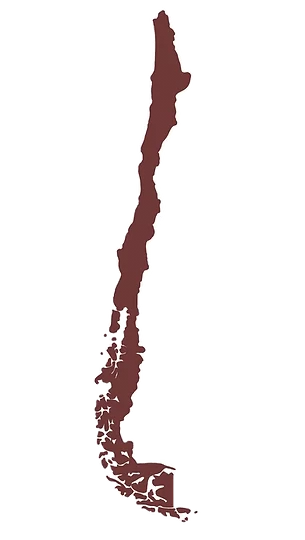

I moved to Canada in the 1970s at 9 years old with my father, mother, and sisters. We fled Chile as refugees to escape the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, who had come to power in a coup on September 11, 1973. My father had supported the Socialist Party and was later imprisoned for political reasons. Thankfully, he was not one of the thousands killed or simply disappeared by the regime. It was after his release that we escaped to Canada.

During my dad’s imprisonment, I was terrified that we would be rounded up as well. The soldiers would visit me in my nightmares, as I envisioned them breaking into our home. The relief I felt as our plane took off from Chile was palpable. Moving to Canada lifted a weight from me and I was finally able to rest. I can recall this feeling even now, as the decades have fled by. I am forever grateful to Canada for having rescued my family.

My father knew intimately what it was like to be a refugee, already having fled from Hungary to Chile as a child of World War Two. He was Jewish and survived the war with a Lutheran family when his family was sent to the camps. His advice led the way. He told us to integrate, adapt, and learn the language. As soon as we arrived in Vancouver, we were sat in front of Sesame Street to learn English. I spent a year in English as a second language classes while my younger sisters adapted even faster. Prior to learning English, I hadn’t even believed it was possible to think in a language other than Spanish. While being able to think in a different language is a small adjustment, it is a signal that an immigrant is becoming a different person. Aside from just signaling greater fluency, language is fundamental to the way we think. Learning a new language opens you to a world of new understanding.

Although I took my father’s advice and integrated into my new country, I still wished to remain connected to my Chilean background. I participated in the Chilean exile community in Vancouver, including attending political events. The same divisions present in Chilean politics manifested into divides within the exile community. The dictatorship was perceived as black and white from those exiled by the coup. This tends to be true of most diaspora politics. The refugee communities are composed of only those who fled the regime and do not represent all the political views within a country. Returning to Chile for the first time years later and reuniting with the family members that had stayed behind and supported Pinochet, I gradually came to realize that the situation was not as black and white as I had thought. Many within Chile supported Pinochet despite the repressive nature of his regime, painting it instead in shades of gray. I saw reconnecting with my family, who had remained and supported Pinochet, as my way of helping to repair the social fabric that had been torn by the coup.

Because of the way politics had affected me personally, I had a desire for understanding that eventually drove me to get my degree in political science. As an adult, I have researched and written about Chile and Pinochet’s dictatorship and done work on other similar conflicts. It is my belief that although regimes like Pinochet’s have committed terrible crimes which should be condemned, that should not close off the possibility for dialogue and negotiation. In order to facilitate change, you have to be able to understand the military and regime from an insider perspective and then work across the aisle. Colleagues of mine have improved human rights standards by working with the armed forces rather than against them. This informs my work with non-state, terrorist, or insurgent actors arguing that there is space for dialogue that also holds them to account for their actions. I believe that this is a legitimate path to peace. The political turmoil I experienced changed my path in life, and without it, I most likely would have chosen to do something else with my career.

I am still an outsider here in Canada, but I no longer belong in Chile either. While the ambiguity of not knowing how to define myself was something I struggled with in my early years, it gave me a different perspective on the world. Eventually I learned to be at peace with this ambiguity and with always being different from those around me. Like most immigrants, I will forever have a foot in two different worlds.

Please note that certain facts have been altered for anonymity

This story is a collaborative effort between Sophia Vitter and Gabriel Martinez